The questions having to do with an upturn in interest rates—whether, when, by how much—continue to attract a great deal of attention from market participants. Of course paying close attention to interest rates makes sense for bond investors because interest rates are the primary driver of total returns on fixed-income investments. Equity investors, though, should focus more on the forces that drive increases in net cash flows, namely supply and demand conditions that affect things like per-unit profits and sales volume.

That’s true for real estate investors no less than for investors in other equity asset classes. The primary driver of real estate returns is increases in net operating income, especially effective rent growth and occupancy rates. I wish I could stamp out permanently the idea that real estate is analogous to fixed-income investing: as I pointed out in a Market Commentary published last week, real estate should provide strong capital appreciation as well as strong current income, so if your real estate manager is trying to convince you that real estate, like bonds, shouldn’t be expected to appreciate in value, then you should probably consider finding a different real estate manager.

An increase in market interest rates can affect real estate returns in five main ways—two of them bad, three of them good:

- The value of any asset is equal to the sum of future cash flows produced by that asset, with each future cash flow discounted to its present value. Any change in interest rates will affect discount rates. This is the primary source of the wrong-headed belief that an increase in interest rates can be expected to reduce property values: if real estate were a fixed-income asset, then an increase in discount rates would bring down the present-discounted value of future net operating income. Fortunately, in the world of actual performance this effect is generally outweighed by other countervailing effects.

- Also, when real estate owners can borrow capital only at variable interest rates, and/or must borrow additional capital, an increase in interest rates will increase borrowing costs. This is the second main reason that market participants believe real estate owners will be hurt as interest rates rise.

- On the other hand, anyone who has already borrowed what they need at a fixed interest rate will actually be better off when market interest rates rise. If your interest rate is fixed, then the market value of your debt actually declines. If you’re a company, then your company’s balance sheet just got stronger, because the market value of your liabilities went down. That’s just the flip side of point #1: if you’re the owner of a fixed-income instrument (meaning a lender at a fixed rate), an increase in the discount rate hurts—but if you’re a borrower at a fixed rate, an increase in the discount rate helps.

- Moreover, property development is even more capital-intensive than property ownership, so an increase in interest rates is likely to make it more expensive for developers to borrow the money they need to increase supply. If you already own property, that constraint on new supply will generally help you by boosting effective rent growth, occupancy rates, and property values.

- Finally, and perhaps most importantly, a change in market interest rates is likely to be a reflection of macroeconomic conditions—and, in particular, an increase in market rates is often a signal that macroeconomic demand conditions are strengthening. The market interest rate is simply the market price for borrowed capital; market prices go up when demand goes up relative to supply; stronger macro conditions mean that people are buying more stuff, which makes companies want to borrow more for things like building factories. As macro conditions strengthen, so often does the demand for real estate, leading to increases in effective rents and occupancy rates.

It should be clear that nobody can give a theoretical answer to the question whether an increase in interest rates will help or hurt real estate owners: the answer depends on which dominates in the real world, the first two (bad) effects or the last three (good) effects. So let’s see whether some actual data can help us sort them out.

Let me start with the idea that an increase in interest rates will hurt real estate owners by increasing borrowing costs (effect #2). Maybe that’s true of some real estate owners, but for equity REITs traded on U.S. stock exchanges, it’s clearly false as a general rule. I looked at data that S&P Global Market Intelligence pulled from quarterly 10-K reports filed by individual listed equity REITs during the 18¾ years 1998Q4-2017Q2, more than 8,500 reports in all. The median share of total debt that was at a fixed interest rate was 83%, and almost one-tenth of the reports I looked at showed that 100% of total debt was fixed-rate; only about one-tenth showed a REIT with more than half of its debt at variable interest rates.

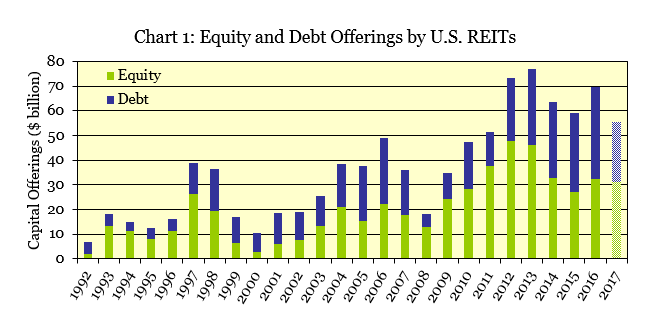

Clearly, listed equity REITs have protected themselves to a great extent from an increase in borrowing costs by locking in their existing debt at fixed interest rates; on top of that, whenever market interest rates increase, the market value of their fixed-rate debt declines, which actually strengthens their balance sheet (#3). What about new borrowing? Well, if debt capital becomes expensive, exchange-listed REITs can raise other forms of capital—chief among them, of course, they can issue equity. Chart 1 shows that listed REITs have had good access to both forms of investment capital, with the annual equity share ranging from 27% to 75% depending on market conditions. As Greg MacKinnon of the Pension Real Estate Association (PREA) observed, “With access to the public markets, REITs have a built-in advantage in times of constrained credit through the ability to raise capital via seasoned equity or unsecured bond issues.”

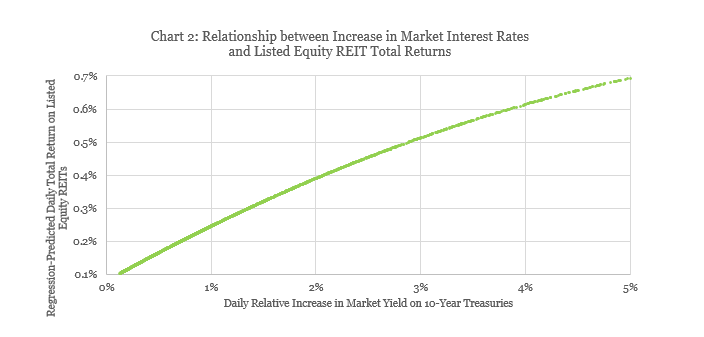

It's difficult to sort out the relative importance of each of the five effects mentioned, but their individual contributions aren’t nearly as important as the bottom line: what happens to REIT returns when market interest rates increase? I’ve studied it many different ways (and so has my colleague Calvin Schnure—see, for example, his recent market commentary focusing on REITs’ use of debt), so here’s just one way of looking at it: I regressed daily total returns of listed U.S. REITs on the daily change in the market yield for 10-year U.S. Treasuries. The slope is positive, meaning that listed REIT returns have tended to be positive when market interest rates are increasing. The intercept is positive, too, meaning two things: listed REIT returns have tended to be positive regardless of whether interest rates are changing or not, and they have tended to be positive even when interest rates were declining, though their returns have tended to be negative when the decline in interest rates was particularly strong.

To be clear, the data I used to compute that regression have encompassed all of the days when interest rates were going up, including the “taper tantrum” of May-June 2013. The data don’t say that REIT returns have to be positive when interest rates go up—but they do say that an increase in interest rates is usually associated with positive returns for investors in listed REITs.

More importantly, that positive relationship holds up even when I restrict my analysis to only those days on which interest rates increased: that is, it’s not simply that the days when discount rates and borrowing costs increased were outweighed by the days when they declined. From the beginning of 1999 through the end of August 2017 there were 2,085 days when the market yield on 10-year Treasuries increased, and Chart 2 shows the regression relationship based on the total returns of the FTSE NAREIT All Equity REIT Index on those days. (I added a quadratic term because some people have said that a small increase in interest rates wouldn’t hurt REITs much whereas a sharp increase would.) As you can see, the regression relationship shows that the total returns on listed equity REITs have tended to be positive on days when interest rates increased, and more positive on days when interest rates increased more.

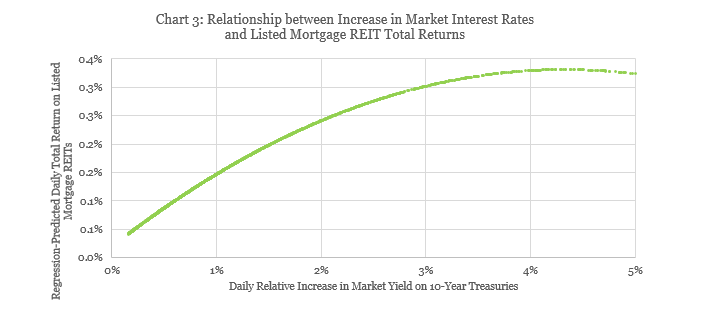

Chart 3 shows the regression relationship based on total returns of the FTSE NAREIT Mortgage REIT Index on the same 2,085 days when market interest rates were increasing. As with listed equity REITs, total returns on listed mortgage REITs have tended to be positive on days when interest rates increased (and more positive on days when interest rates increased more, over most of the range of historically observed increases), but listed mortgage REIT returns were generally not as strong as listed equity REIT returns during the 1999-2017 period. (My colleague Calvin argues, however, that the mortgage REIT industry is very different now than it was earlier in that period: in particular, that REITs focusing on agency-backed mortgages have come to dominate the listed mortgage REIT industry, and that agency-backed mortgages have provided better long-term average total returns to investors than the non-agency-backed mortgages that used to predominate.)

To summarize, market participants often cite two stories to explain why they may expect REITs to be hurt when interest rates increase: the first story treats real estate as if it were a fixed-income asset rather than an equity asset, and the second story treats real estate owners as if they hold only floating-rate debt and must increase their borrowing even as borrowing costs rise. Those are perfectly reasonable stories, but they’re nothing more than stories—and stories that aren’t supported by actual data shouldn’t really be used for anything other than putting children to sleep at bedtime.

It turns out that, historically, those negative effects have generally been dominated by the positive effects of an increase in interest rates: shrinking the liability side of the balance sheet, reducing new supply in the property market, and/or signaling stronger macro demand conditions and therefore stronger effective rent growth and occupancy rates. An increase in interest rates might be cause for concern if it were predicted to come with no accompanying increase in net operating income—but it’s those changes in net operating income, not the interest rates themselves, that should attract the closest attention of investors in any equity asset such as real estate.

By the way, if you have any comments or questions, drop me a note at bcase@nareit.com.