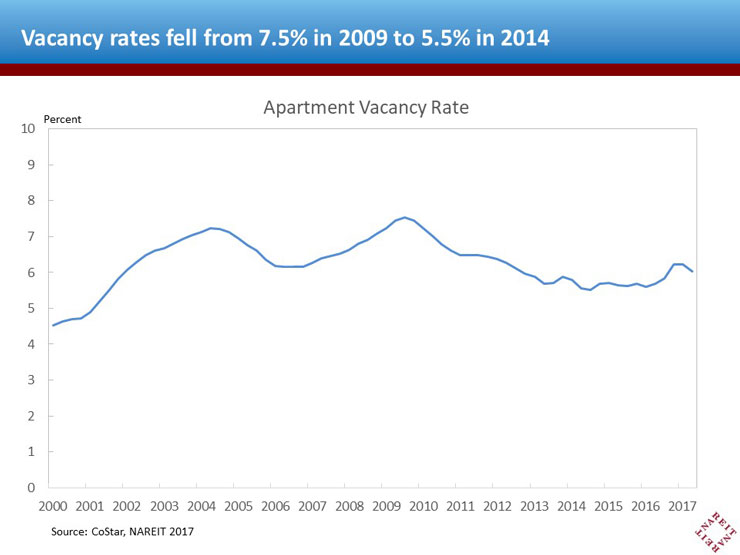

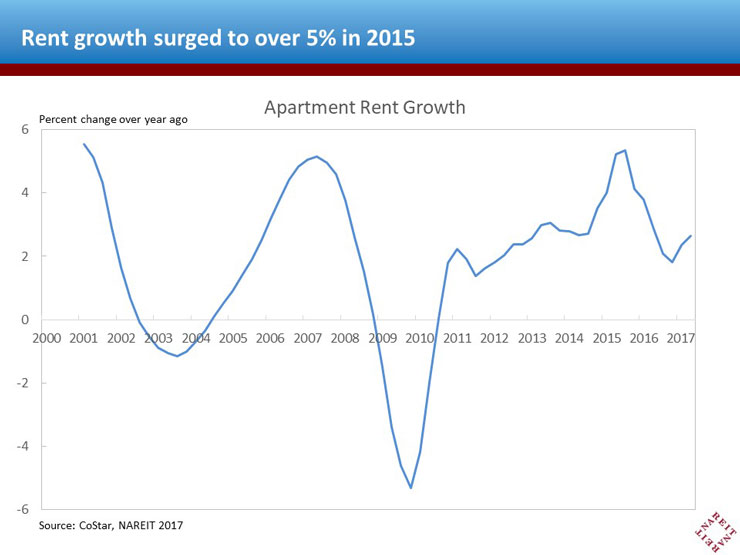

Apartment markets across the country have been tight since the housing crisis, with low vacancy rates and high rents being the norm. Millions of households were unable to buy a home due to damaged credit or lack of a down payment, or perhaps were unwilling to take on the financial risks of homeownership, and chose to rent instead. Apartment vacancy rates declined steadily, from a peak of 7.5 percent in 2009 to reach a low of 5.5 percent in 2014. Rent growth surged to over 5 percent in 2015, before slowing to about half that pace in 2016 and the first half of this year.

Apartment REITs have benefitted, with total Funds from operations (FFO) increasing more than 140 percent, from $2.2 billion in 2009 to $5.4 billion in 2016 (See NAREIT T-TRACKER for complete data). Increases in construction of new apartments have challenged the market, however, prompting many analysts to ask whether a wave of new supply threatens to swamp the market, possibly leading to rising vacancy rates, declines in rents and perhaps even falling property values. Indeed, vacancy rates nationwide did tick up a bit in 2016 before turning back down this year.

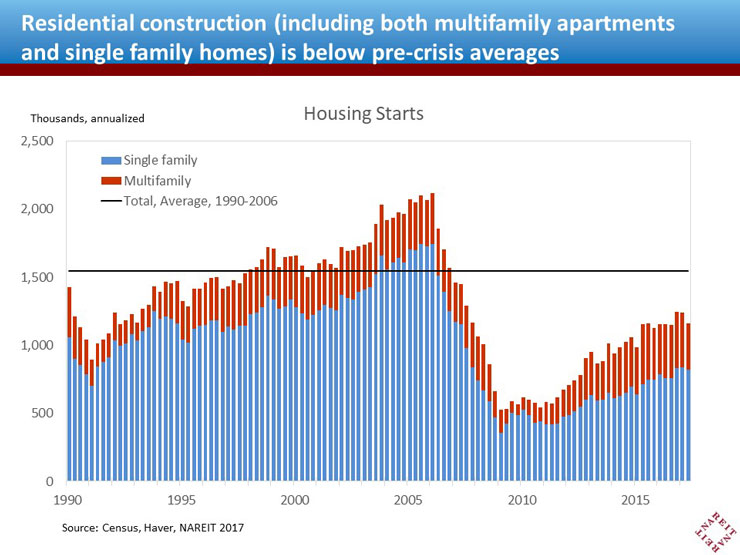

The increase in the pace of new construction has been significant. Construction starts on new apartment units reached an annual rate of 400,000 over the first half of 2017, more than double the rate of construction five years earlier. Yet despite this increase, the overall pace of residential construction—including both single-family homes and multifamily apartment units—has not yet returned to the rate from 1990 through 2006. This restrained supply has contributed to an overall scarcity of housing.

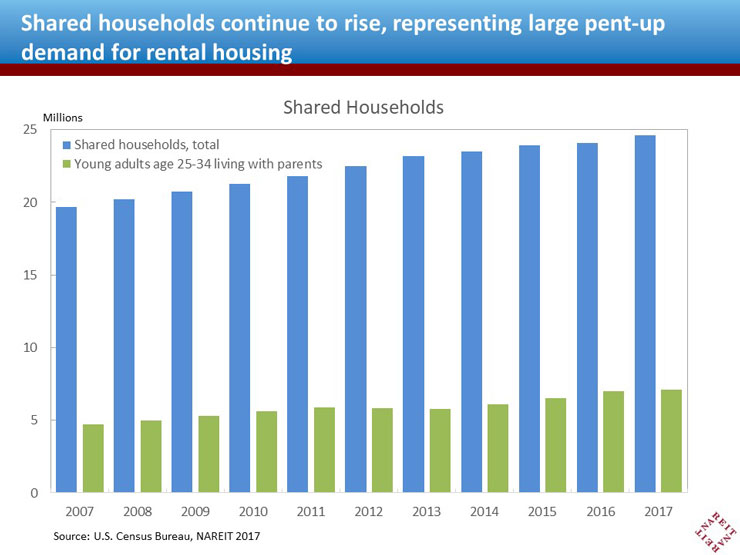

This scarcity is manifest in “shared households”, that is, those households that include an additional adult over age 18 other than the head of household or the spouse or partner of the head of household. These shared or “doubled-up” households represent future demand for apartments, as many of the additional adults living in such doubled-up households will eventually move out to rent their own apartment. (My estimate of pent-up demand is based on the increase in shared households compared to pre-crisis. Some people may choose to double-up to save expenses, as a lifestyle choice or for other reasons. History demonstrates, however, that underlying patterns of housing choice generally return to long-term trends--the main question is, how quickly does this happen. Among the households expected to emerge in the future, some may become homeowners, but most will likely be renters first until their income and savings are sufficient that they can consider buying.) The number of shared households rose from 19.7 million in 2007, representing 17.0 percent of all households, to reach 21.8 million households (18.3 percent of total households) by 2011.

An analysis that I conducted in 2012 concluded that the “pent-up demand” for apartments that these shared households represent would keep market conditions firm, even in the face of rising construction (see, “When Living with the In-Laws Gets Old: The Outlook for Multifamily Housing 2012-2017”). I estimated in 2012 that the pent-up demand represented a need for at least 3 million additional housing units (apartments or single-family homes) as market conditions eventually returned to pre-crisis norms. Under various scenarios of household formation and apartment and housing construction, I demonstrated that it would take more than five years for the excess demand to be fulfilled.

It has been more than five years since I prepared that analysis. What is surprising about current market conditions is that not only does the pent-up demand remain large, it has even continued to grow. The Census Bureau recently reported that, as of April, 2017, the number of shared households had risen to 24.6 million, or 19.4 percent of all households. Included among these shared households are those with young adults age 25-34 who are living with their parents (green bars). Like total shared households, the number of adults living with their parents hit a record high in 2017, of 7.1 million, compared to 4.7 million prior to the housing crisis.

These trends demonstrate that housing markets remain tight, even accounting for increased construction. Moreover, the excess demand for housing is likely to continue for quite some time. In fact, at the current pace of apartment construction, it would take nearly 8 years to build enough units to provide space for all the potential renters represented by the elevated level of shared households versus pre-crisis figures—and that’s not even taking into consideration population growth that will generate additional demand.

Vacancy rates are likely to remain low as adult members of these shared households eventually strike out on their own. The experience of the past five years cautions, however, that the process may take longer than anticipated. This suggests that low vacancy rates will be here for quite some time, and the outlook for Apartment REITs is favorable.