Private Equity Real Estate Managers are Turbocharging their Manipulation by SLOCking

I'll never understand how supposedly "sophisticated" institutional investors have allowed themselves to fall into the trap of using IRR as an investment performance metric, notwithstanding their fiduciary responsibility to make investment decisions in the best interests of their clients. Ludovic Phalippou famously said in a paper published almost a decade ago that "IRR is probably the worst performance metric one could use in an investment context," partly because it "can be readily inflated." Phalippou also mentioned that IRR "exaggerates the variation across funds, exaggerates the performance of the best funds, … and provides perverse incentives to fund managers."

Phalippou's 2009 paper is among those in my annotated " Bibliography on Performance of Private Equity Funds " with key quotations and web links. While Phalippou’s focus was on private equity investments in non-real-estate assets, especially buyouts and venture capital, it’s important for real estate investors to understand that manipulating IRR is just as big a problem for private equity real estate (PERE) as it is for other PE investments.

Recently you may have noticed articles published in the financial press about institutional investors' increasing alarm with respect to the use of "subscription lines of credit" by PE and PERE managers . A subscription line (or SLOC) is a form of debt securitized by the capital commitments that investors have made to a PE or PERE manager. Managers use the debt to start investing before they actually call the committed equity capital from their investors

Of course, if the investment goes bad then the investors are on the hook for it. The increased risk is not the only SLOC-based problem that should bother investors, however: another problem is that SLOCs give PE/PERE managers one of the most effective means of manipulating IRR, to their own benefit but to the detriment of pretty much everybody else. In other words, as Phalippou pointed out, IRR “can be readily inflated”—and SLOCs are just about the easiest way to do exactly that.

I was asked the other day for an illustration of how SLOCking is used to manipulate IRRs, making it appear that the managers have provided better investment returns than they really did, so I thought I would share a simple example. (The point of this example is to illustrate the mathematical quirk that incentivizes the manager behavior, not to be realistic.)

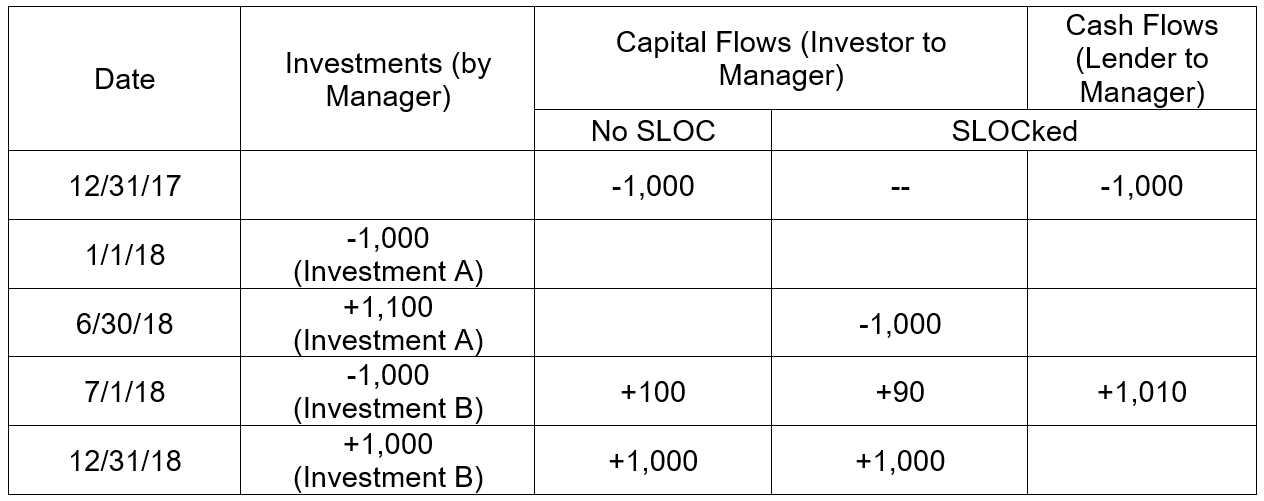

Table 1 summarizes my illustrative situation. The PE/PERE manager is going to make two investments: Investment A is modestly successful, whereas Investment B recovers its outlay but returns no gain. To simplify the illustration, the two investments will be sequential rather than simultaneous. Before investing the PE/PERE manager raises a fund--that is, the manager receives capital commitments from an investor.

It’s important to realize that investors face very substantial penalties if they fail to meet a capital call, so it’s very common for them to hold the committed capital in cash while waiting for it to be called. In other words, after they’ve committed the capital, investors don’t generally benefit from any delay between the commitment date and the capital call—but that delay is exactly what makes SLOCking work.

The importance of subscription lines of credit in manipulating IRR comes from the fact that they enable the PE/PERE manager to manipulate the timing of cash flows experienced by the investor without affecting the actual investment performance--whereas with no subscription line of credit the cash flows that the investor experiences must closely match the actual investment cash flows. Let’s go through the illustration to see how that works.

- With no SLOC, the PE/PERE manager raises $1,000 in equity capital, issues a capital call in time to make the first investment (12/31/17), uses the $1,000 equity capital to make Investment A (1/1/18), sells Investment A for $1,100 (6/30/18), re-uses the $1,000 equity capital to make Investment B and simultaneously distributes the $100 gain from Investment A (7/1/18), sells Investment B at no gain (12/31/18), and returns the original $1,000 of equity capital to the investor. Put the investor’s cash flows (-1,000 on 12/31/17, +100 on 7/1/18, +1,000 on 12/31/18) into an Excel spreadsheet, use the =XIRR function, and you find IRR = 10.51 percent.

- SLOCked cash flows: Use the same actual investment cash flows, but this time the PE/PERE manager makes Investment A using a subscription line of credit rather than the equity capital committed by the investor. That doesn't help the investor--first because the investor has to keep the committed capital in cash to ensure they can meet the capital call, and second because the interest cost will come out of the investor's gains. Specifically, let's say that the investor's equity capital is not called until 6/30/18. In other words, from 12/31/17 through 6/30/18 the only purpose of the capital commitment was to secure the loan of $1,000 on 12/31/17, which is repaid with $10 interest on 7/1/18 simultaneously with the use of the investor's equity capital to make Investment B. This time the return to the investor is actually less: the investor gets a distribution on 7/1/18 of only $90 (the $100 gain on Investment A minus the $10 interest cost of the loan). The investor is unquestionably worse off, but what do you suppose happens to the IRR? It's based on the timing of the investor's cash flows--not the timing of the investment manager's cash flows or of the investor's capital commitments--so your Excel spreadsheet would use -1,000 on 6/30/18, +90 on 7/1/18, and +1,000 on 12/31/18, which would give you ... wait for it ... IRR = +20.56 percent!

Wow. The actual investment performance is worse, but the metric used to evaluate that performance has nearly doubled. That's pure manipulation, but it means that the investment manager--who is supposed to be exercising fiduciary responsibility by making investment decisions on behalf of the investor--gets to claim that they're really good at what they do, when the truth is that, in this example, the performance of the actual investments was absolutely ordinary.

A set of academics noted this, in a comment about VC managers that applies equally to all managers of private (illiquid) investments including those in real estate: "It is often said that a venture capitalist has two jobs: investing in entrepreneurial firms and raising their next fund. That next fund provides a steady stream of performance-insensitive management fees for at least ten years. Performance evaluation by the capital providers to limited partners is thus an area ripe for manipulation." (That 2014 paper by Chakraborty & Ewens is part of the annotated bibliography that I mentioned previously)

As I mentioned, most of the unfavorable press regarding SLOCs focuses on buyouts and VC rather than real estate; real estate investors, however, need to pay particular attention to something that is widespread in the PERE world but amounts to little more than a slight variation on SLOCs: I’m referring to forward commitments. In real estate, the PERE manager may enter into an agreement to purchase a property that is still under construction: the agreement becomes binding early (say, 1/1/18 in my example shown above), but the transaction isn’t recorded until after the building is completed (say, 6/30/18 in the example.) As with the SLOC, if the investment goes bad then the investors are still on the hook for it—and, of course, the use of a forward commitment enables the PERE manager to delay the recognition of the initial cash flow, thereby jacking up the IRR.

The illustration makes an important point: that IRR can be so easily manipulated because it is so sensitive to the timing of cash flows. Certainly many investors (and, of course, their investment consultants) are aware of this problem, and for that reason many of them prefer to focus on “equity multiples” such as Total Value to Paid-In (TVPI), which measure how much capital is returned to the investor over the full life of the capital commitment, with current valuations of still-active investments standing in for the estimated value of eventual distributions from those investments. TVPI is generally seen as a better performance measure (in fact, the Institutional Limited Partners Association calls it “perhaps the best available measure”) because it isn’t sensitive to the timing of cash flows. Does that solve the problem?

No, it doesn’t, for two reasons. First, if IRR is a poor measure because it rewards the investment manager for delaying the capital call even when the delay doesn’t benefit the investor, TVPI is a poor measure for basically the opposite reason: it fails to penalize the investment manager for delaying the distribution of capital back to the investor. Here’s what I mean: in the illustration above, the investor paid in $1,000 and received $1,100 in total value, so TVPI is 1.10. (With the SLOC it would have been only 1.09.) But what if the investment manager had held on to the capital for another year? That’s bad for the investor because it prevents him from investing it somewhere else and earning a return on that capital—yet the TVPI is unchanged at 1.10.

The second problem with TVPI (and similar measures) is exactly the same as the problem that has always existed with IRR: neither measure incorporates any concept of risk. Getting a TVPI of 1.10 from investing in U.S. Treasuries is a whole lot better than getting the same TVPI from making a highly leveraged speculative investment that depends on timing the market perfectly. Any “performance” measure that fails to adjust for risk is worse than useless—regardless of whether the additional risk comes from a SLOC, a forward commitment, or any other source.

Investors in public equities have benefited from unambiguous performance data extending back well over a century, while investors in REITs have benefited from equally unambiguous data extending back to January 1972, when Nareit started producing what is now the FTSE Nareit U.S. Real Estate Index Series. When you see a report that, for example, REIT returns have averaged 11.74 percent per year over the last 45-plus years, it means that an investor could actually have replicated the performance of the index (net of transaction costs) from the end of 1971 and seen their wealth increase from, say, $1,000 to $176,210 at the end of July 2018. In contrast, when a private equity real estate investment manager says they achieved a “return” of 11.74 percent, there’s a pretty good likelihood they don’t mean that any investor could have grown her wealth by more than 176 times over that same 45+-year period. Instead, in many cases investors will find that SLOCking, forward commitments, or other manipulations have been used to make the “return” figure appear more impressive than it really is—while increasing both the investor’s risk of loss and the manager’s “performance” compensation.

A couple of years ago, at a panel discussion of PE managers organized by CFA Society Washington DC, I asked how important it is for a PE fund manager to ensure there's an early distribution to the investor, thereby locking in a high IRR that basically won't decline regardless of how poorly the fund performs over the remainder of its life. They all looked at each other, nodded, and said—explicitly—"it's absolutely crucial." My guess is that, if they weren't already using subscription lines of credit to manipulate their IRR, every one of them is doing so now. Because in private equity—and in private equity real estate, but not in REITs—it's so easy.

If you have any questions or comments, please drop me a note at bcase@nareit.com.