Hospitality Properties Trust has built a time-tested business specializing in suburban hotels.

Throughout much of this recovery, high-end hotels in urban markets have outshined their lower-priced and suburban counterparts in terms of revenue growth.

Throughout much of this recovery, high-end hotels in urban markets have outshined their lower-priced and suburban counterparts in terms of revenue growth.

Recently, though, the tables have turned, and that’s good news for Hospitality Properties Trust (NYSE: HPT), which since its IPO in 1995 has focused almost entirely on select-service and extended-stay hotels in suburban markets.

The Newton, Massachusetts-based REIT owned just 53 Courtyard by Marriott hotels when it went public two decades ago. Its holdings were spun out of a health care REIT managed by The RMR Group, which is HPT’s external manager.

As of late last year, HPT owned 302 hotels and 193 travel centers in the United States, Puerto Rico and Canada. Its upscale hotels cater primarily to domestic business travelers, the road-warrior types. They are largely located in the close-in suburbs of major cities near corporate business parks.

In recent years, HPT has seen other big investors warm to select-service hotels, which tend to provide a higher return per invested dollar than full-service hotels, according to David Loeb, a senior real estate research analyst at Robert W. Baird. Private-equity firms Starwood Capital Group, Clearview Capital and Blackstone Group have been among the top buyers of select-service hotels.

“Before it was fashionable, we liked the select-service” niche because of its stable cash flow, says John Murray, HPT’s president and chief operating officer.

Select-service hotels, which fall into the limited-service category, typically have fewer rooms and amenities than full-service hotels, making them simpler and less expensive to operate. Many travelers like the simplicity, not to mention the price tag, of select-service brands, which include Courtyard, Hyatt Place and Candlewood Suites.

Hotel investors appear to like HPT’s scaled-back approach in the current environment, too. According to NAREIT data, the lodging sector overall was down 19.5 percent through the first 11 months of 2015. HPT’s stock price fell roughly 4 percent in the same timeframe.

Hotel Recovery Trickling Down

“For a lot of consumers, select-service hotels provide the kind of comfort they need without a lot of the extra things,” such as concierge desks and 24-hour room service, that factor into the room rates at full-service hotels, Loeb explains.

“For a lot of consumers, select-service hotels provide the kind of comfort they need without a lot of the extra things,” such as concierge desks and 24-hour room service, that factor into the room rates at full-service hotels, Loeb explains.

When hotel demand is strong, select-service hotels may have less upside potential than full-service hotels because of their smaller room count, according to Murray. But when demand is soft, select-service hotels tend to hold up relatively well because of their lower fixed costs, he adds. As a result, their cash flow is more predictable through industry cycles, according to Murray.

Extended-stay hotels, which feature in-room kitchens and cater to travelers booking for a week (or more) at a time, are a form of select-service hotel. They include brands like Residence Inn by Marriott, Staybridge Suites and Sonesta ES Suites.

Select-service hotels “may have less upside than full-service hotels during the good times, but they generally have continued to make money, perhaps less than they had been making, even during the bad times,” says Murray, who is also an executive vice president with The RMR Group.

According to a report by Green Street Advisors, hotel REIT portfolios are largely comprised of higher-priced hotels and concentrated in gateway markets. Lately, though, lower-priced hotels and those in suburban markets have seen more-robust growth levels as measured by revenue per available room, or RevPAR.

Last year, through October, the “economy” segment of the hotel industry had the highest rate of RevPAR growth, while the “luxury” segment had the lowest rate, according to the Green Street report, which cites data from Smith Travel Research.

“We started the recovery in the hotel sector in 2010, and the high-end of the sector had been leading the way. Now, we are seeing the recovery filter down to other segments,” said Lukas Hartwich, a lodging analyst at Green Street.

More Bang for the Room

Over the past five years, HPT has spent nearly $1 billion to renovate its hotel portfolio and is now reaping the rewards. Last year, its hotel portfolio had an average occupancy rate of just over 77 percent, through September. Strong occupancy and rate growth contributed to a 9.5 percent increase in comparable-hotel RevPAR for the year-to-date period through September 2015, versus the same period in 2014.

Over the past five years, HPT has spent nearly $1 billion to renovate its hotel portfolio and is now reaping the rewards. Last year, its hotel portfolio had an average occupancy rate of just over 77 percent, through September. Strong occupancy and rate growth contributed to a 9.5 percent increase in comparable-hotel RevPAR for the year-to-date period through September 2015, versus the same period in 2014.

For the past three years, HPT’s RevPAR growth has exceeded the hotel industry’s average RevPAR growth, as measured by Smith Travel Research, by about 2 percentage points annually, according to the company.

“If you have high occupancy rates and can raise rates, you don’t need to hire more people to staff your hotels. You are simply getting more revenue per room, which mostly falls to the bottom line,” Murray says.

Yet, six years into the hotel industry’s recovery, some investors have begun to worry that a peak is imminent. Hotel fundamentals have slowed recently, partly as a result of weaker international travel to the United States tied to a strong U.S. dollar, according to Green Street.

“We are in year six of the cycle, and investors are not really sure what is around the corner. That uncertainty, coupled with slowing fundamentals, has investors scared when it comes to lodging,” says Hartwich of Green Street.

One way HPT has sought to insulate itself from volatility in the hotel business is through the types of management agreements it negotiates with brands that operate its properties. All of its hotels are operated by major brands, as opposed to the third-party management groups that serve many other owners.

Under most of its management agreements, operators must pay HPT a minimum annual return before collecting their management fees. Many of its agreements call for security deposits or guarantees, out of which operators must pay HPT if hotel profits fall short of the yearly minimum returns. “That aspect of our agreements helps us if there is a recession and there is pressure on hotel operations. We have some confidence that we will still get paid even if the hotels don’t quite make enough money” to cover our minimum returns, Murray explains.

Under most of its management agreements, operators must pay HPT a minimum annual return before collecting their management fees. Many of its agreements call for security deposits or guarantees, out of which operators must pay HPT if hotel profits fall short of the yearly minimum returns. “That aspect of our agreements helps us if there is a recession and there is pressure on hotel operations. We have some confidence that we will still get paid even if the hotels don’t quite make enough money” to cover our minimum returns, Murray explains.

“In exchange for that downside protection, we give something up,” in the form of higher-than-normal, incentive-management fees for hotel operators, he adds. “They give us downside protection and, in return, we give them more share of the upside,” explained Murray.

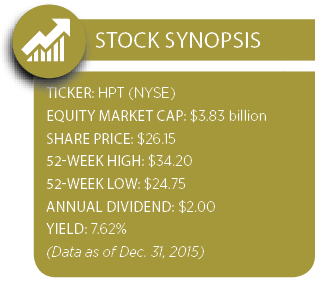

Thanks to the steady returns HPT generates under its management agreements, the company was able to quickly re-establish its dividend after cutting it during the last recession. It now pays one of the highest dividends among hotel REITs, says Rod Petrik, a managing director at Stifel Nicolaus. Its annualized dividend was $2 a share as of the third quarter of last year.

External Management

Another factor that distinguishes HPT from most other stock exchange-listed hotel REITs is its management structure. When the company went public in 1995, many exchange-listed REITs had external managers, which were typically privately held firms.

Today, though, most exchange-listed REITs are internally managed, and HPT has faced some lingering questions about its management structure.

“Externally advised REITs were the norm for a while, but that structure fell out of favor, and investors voted with their feet in favor of internally managed REITs,” says Loeb of Robert W. Baird.

HPT says its management structure is a competitive advantage due to The RMR Group’s depth of management and experience in the real estate industry. Founded in 1986, RMR (formerly REIT Management & Research Inc.) had more than $22 billion in real estate assets under management in the third quarter of last year and 17 offices across the country. The company manages a total of four exchange-traded REITs. It also provides management services to a real estate mutual fund and several real estate operating companies, including publicly traded TravelCenters of America.

HPT says its management structure is a competitive advantage due to The RMR Group’s depth of management and experience in the real estate industry. Founded in 1986, RMR (formerly REIT Management & Research Inc.) had more than $22 billion in real estate assets under management in the third quarter of last year and 17 offices across the country. The company manages a total of four exchange-traded REITs. It also provides management services to a real estate mutual fund and several real estate operating companies, including publicly traded TravelCenters of America.

According to HPT, The RMR Group provides management services to HPT “at costs that are lower than we would have to pay for similar quality services.” Each year, HPT provides its board with an analysis of how its general and administrative costs, which include fees paid to RMR, compare with those of net lease and lodging REITs in general when measured as a percentage of total revenues and assets under management.

“Our administrative costs tend to be less than comparable costs at our competitors as a percentage of assets and as a percentage of revenues,” Murray says.

HPT has taken other steps to address investor questions over its management structure. Last year, the company announced that it, along with its three sister REITs, would acquire about half of RMR, creating a closer alignment of interests. In December, RMR began trading on the NASDAQ and distributed roughly 7.5 million shares of common stock to shareholders of the four REITs.

“We’ve tried to alleviate the most important concerns that people have, but our management structure is still a unique structure, and there are some institutional investors who prefer not to invest in externally advised REITs,” Murray explains.

Rising Rates Not a Worry

Of course, some investors are also worried about the impact of the Federal Reserve’s rate hike at the end of 2015 as well as the recent slowdown in hotel fundamentals.

According to Murray, HPT has been largely insulated from the slowdown in international travel to the United States because its hotel portfolio is concentrated in suburban markets.

The company does own several full-service resorts, which include properties in Hilton Head, S.C.; San Juan, Puerto Rico; and Kauai, Hawaii. Last year, its Hilton Head resort, which largely serves domestic tourists, outperformed its resorts in Puerto Rico and Hawaii, Murray notes.

“That’s perhaps a reflection of things being better with the U.S. economy than they are in Europe and Asia and of the impact of a strong U.S. dollar,” he says.

HPT’s concentration in suburban markets has also helped to insulate the company from new competition. Six years into the hotel-industry recovery, overall supply growth is still low, but it is picking up in urban submarkets, according to Green Street. In addition, new supply is concentrated in the limited-service segment, reports Green Street.

“So far in this cycle, supply growth has been a larger issue in certain key urban markets and not so much of one in suburban America,” Murray observes.

New York City, for instance, has seen an “onslaught of new supply,” according to Green Street. “For the first cycle since I can remember, New York City has had flat or declining RevPAR. That is not caused by Airbnb or a strong U.S. dollar, but the new supply of Hilton Garden Inns, Residence Inns” and other types of select-service hotels, Murray says.

In 2016, Murray expects HPT to have another good year if the U.S. economy continues to grow at its current pace and employment trends remain generally positive, although he says revenue growth may slow a bit.

According to Green Street, U.S. companies, other than those in commodities-related sectors, are more profitable than ever, which bodes well for business travel. What’s more, Green Street reports that leisure travel, which accounts for 25 percent of hotel demand, is improving as a result of a better job market and rising incomes.

“We have been outperforming historical run rates for a number of years now and, although we anticipate another very good year in 2016, the pace of growth, but not our outperformance, may slow a little,” said Murray.

Higher interest rates, he adds, shouldn’t alarm hotel REIT investors. Rising interest rates, according to Murray, are typically a reflection of strong economic growth, and hotel operators have the ability to quickly capitalize on robust demand by raising room rates.

“Rising interest rates, in most cases, mean a strong, growing economy, which should mean we are able to grow revenues and more than offset the impact of rising rates,” he said.

Hospitality Property Trust Keeps on Truckin’

Hospitality Property Trust Keeps on Truckin’

What also sets HPT apart from its hotel REIT peers is the fact that it owns more than 190 travel centers, a business that, according to Murray, has parallels to the hotel industry in terms of the hospitality services it provides to professional truck drivers.

The company made its foray into the travel center business in 2007 when it bought TravelCenters of America, one of the country’s largest operators, from a group of private investors. For REIT compliance reasons, it subsequently spun off TravelCenters’ operating platform and retained most of the real estate.

Under its agreements with travel-center operators, HPT collects base rents and percentage rents tied to increases in non-fuel sales. Its agreements with operators also provide for rent increases tied to capital investments by HPT for property upgrades.

“I like to think of travel centers as being similar to hotels for professional truck drivers,” says Murray, noting that truck drivers can reserve parking spots and showers before arriving at travel centers. They can also make restaurant reservations ahead of time.

Professional truck drivers must adhere to regulations for when and how long they can drive each day, ensuring a steady stream of customers at the travel centers. HPT’s travel centers are located at exits off interstate highways, making them a convenient stop for rest, fuel, shopping, meals and truck-repair services.

“There aren’t a lot of restaurants in downtown areas where you can park a tractor-trailer truck and have lunch,” Murray notes.

HPT generates about a third of its profits from its travel-center portfolio. Last year, the company announced its first acquisition of travel centers since its foray into the market nearly a decade ago. It is acquiring 25 centers for about $279 million from TravelCenters of America through sale-leaseback deals.

Over the next couple of years, HPT expects to buy another half dozen centers from TravelCenters of America, which is developing the properties. However, there is limited development potential in the travel-center business, because of strong barriers to entry, Murray explains. It is difficult, he explains, to get new projects permitted and to find tracts of land that are large enough to accommodate them. TravelCenters of America, he notes, has grown its real estate holdings mostly by acquiring centers from mom-and-pop operators and renovating them.

“When the interstate highway system was developed under the Eisenhower administration, there were a lot of exits with little or no commercial development surrounding them, but that isn’t the case today,” Murray says.

“You’ll see us grow primarily in the hotel space,” he adds, “but every now and then, we will take advantage of an opportunity, where the returns are good, to add a handful of travel centers.”