Prologis builds the first U.S. warehouse serviceable by trucks on two floors.

Last October, at a former shipping container storage site about five miles south of downtown Seattle, the finishing touches were made on a three-story distribution center, the first in the United States to have a second floor serviceable by tractor-trailer trucks. The building, dubbed “Georgetown Crossroads,” is owned and managed by leading logistics REIT Prologis, Inc. (NYSE: PLD).

With 590,000 square feet of warehouse space, it offers more than double the capacity of what would have been possible for a one-story building. Yet perhaps most critical is the site’s central location in a metropolitan area of nearly 4 million people, and just a few miles from its ports.

The project’s completion is all part of an effort to meet the seemingly insatiable demand from e-commerce retailers to be closer to their customers to shorten delivery times. Prologis’ clients had been telling its leadership they need this type of class-A space, ensuring a shorter drive to retail consumers’ doorsteps. Such a large land parcel doesn’t come to market often these days in urban locations, where old manufacturing spaces can get converted for office or apartment use. So, if developers are going to answer the call of e-commerce for more infill space—urban parcels that get rededicated—there’s really nowhere else to go but up.

Challenges of scale

“If your customers are telling you, ‘We really need new product, and we want it in major urban areas,’ it’s a challenge to build anything of any scale,” says Hamid Moghadam, chairman and CEO of Prologis. “It just doesn’t exist. So, you have to densify the site.”

Of course, one big driver of demand for new space in close proximity to customers is Amazon, whose Amazon Prime service offers two-hour delivery windows for certain items. Other retailers have been pressured to follow suit.

However, this presents a problem with the old model of using class-A distribution centers built on greenfields on the outskirts of metro areas. Even in areas such as New York, much of its infill area won’t suffice. A large portion of the area’s warehouse capacity is situated in northern New Jersey, making a same-day delivery to the Bronx or Queens much more difficult within a two-hour window, given the distance and traffic.

“If they want to deliver inside their same-day delivery window, they are going to need to be in the city proper,” says Rob Kossar, international director and head of JLL’s northeast industrial region. “The only way to do it in the city, based on the cost and dearth of land, is to go vertical.”

The race to be closer to consumers has driven the likes of Prologis to acquire sites that are more central. “The large e-commerce companies have made a commitment to providing same-day delivery,” Kossar says. “We are on the precipice of some significant demand and it is extraordinarily supply-constrained.”

Despite the growth of e-commerce, it’s still just a fraction of all retail sales. U.S. e-commerce sales rose to $131 billion in the third quarter of 2018, a 15 percent increase from the same period a year earlier, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Yet that still only represented 9.8 percent of all retail sales.

“We are still at the very early stage of conversion of business models from good old-fashioned brick-and-mortar to e-commerce delivery,” says Joshua Harris, a professor at New York University’s Schack Institute of Real Estate.

As e-commerce providers clamor for warehouses, they’ll need typically three times as much space as used by their retail counterparts to be able to sell the same wares, according to Prologis. Industrial real estate as an asset class can’t meet the demand fast enough, with vacancy at historically low levels nationally of 4.3 percent, according to CBRE. “There continues to be a supply-demand imbalance,” says Matthew Walaszek, a senior researcher at CBRE. “It’s sort of a perfect storm for an evolution of development.”

Maximizing a site’s potential

For Prologis, its Georgetown Crossroads project is part of its ongoing strategy to focus on infill locations. In addition to Seattle, the company is also planning to build a multistory warehouse in San Francisco.

“We have really decided to start to take our investing to the urban core,” says Dan Letter, managing director of capital deployment for Prologis’ northwest region. “That is where our customers are going. We want to be there before they are.”

Prologis bought the 13.5-acre Georgetown Crossroads site in 2015 for $24.5 million, which translates to about $42 per square foot. At first glance, that sounds pricey when compared with land purchased for warehouse development. The average land price for single-story warehouse development in the U.S. was about $30 per buildable square foot, according to October 2018 data published by CBRE.

For Prologis, the economics made sense. To start with, the site it bought was paved, lit, and fenced at the time of purchase.

Also, Georgetown Crossroads was unique given its relatively large size in the submarket of South Seattle, where vacancy for industrial has hovered around 1 to 2 percent for the last five years, according to Prologis. The company has bought warehouses in South Seattle over the years, but the challenge has been finding buildings with scale. This is in part due to high demand for existing parcels, but supply is also limited, exacerbated by how old manufacturing spaces in Seattle have also been converted to other uses, such as apartments and office space, Letter notes.

“We thought the market could handle literally two and a half times the amount of industrial space we could otherwise build on a conventional single-story design,” Letter notes. “Realizing where we were in the cycle and the market we were in, we had a strong belief that Seattle had a lot of runway for hyper-growth.”

Lessons from Asia

To build Georgetown Crossroads, Prologis tapped the expertise of its overseas colleagues in Japan. The company has already built 53 multistory distribution centers in Asia. One thing the Japan team stressed: There had to be two ramps.

“It’s really important for users to feel comfortable that if a ramp goes down because of an accident or what may be, that there is access to the other floors,” Letter says.

The ramps were also more of a challenge to build because they must support heavier truck loads and longer lengths in the U.S. versus those of Japan. Trailers in the U.S. are typically 53 feet—not including their 20-foot cabs—compared with a maximum truck length in Japan of 39 feet. That meant the spiral ramps used there are not practical in the U.S. Instead, wider, longer ramps that wrap around rentable building space are needed. It also meant higher-grade concrete and thicker rebar steel than it used in its Japanese warehouses. The ramps and the truck courts are two of the most expensive parts of the design, and U.S. office parking structures weren’t a good comparison as a guide, Letter notes. The ramps and upper docks have to be able to handle much higher loads than conventional office towers, for example.

“In a conventional design, you have concrete sitting on the ground in your truck court,” Letter says. “Here, we’re elevating it.”

Prologis also polled its customers in the U.S., asking them what other features were most important. Maximum clear heights—which can now soar as high as 40 feet for new warehouses—weren’t essential. More important was the column spacing, which is 50 feet by 45 feet on the first two floors.

Generally, tenants will have to make some sacrifices by choosing closer-in locations, Moghadam notes. For example, they won’t find class-A warehouses in the infill locations with 32-foot clear heights.

“You all of a sudden find yourself in a world of tradeoffs,” Moghadam says. “Do you find that brand-new facility, with all the key features, and if you do, where is that going to be? It’s likely to be way out of town, on the periphery, at the next place to develop new product. Or you have to compromise the quality and features of the building and get infill.”

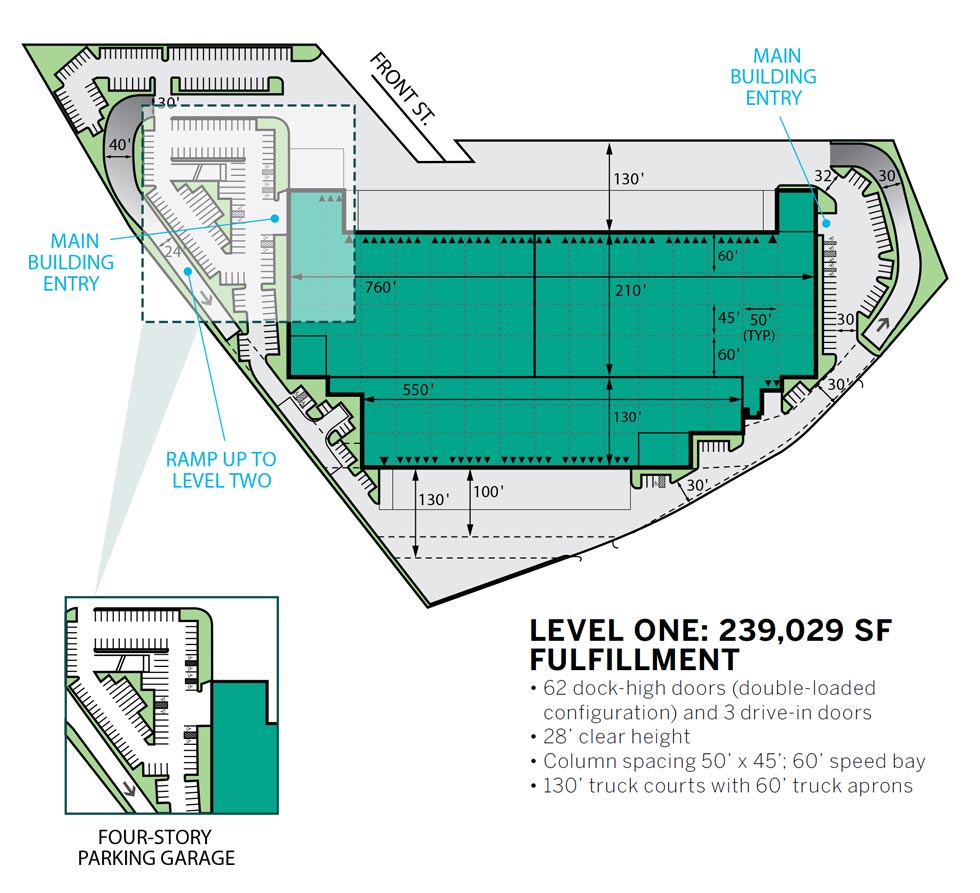

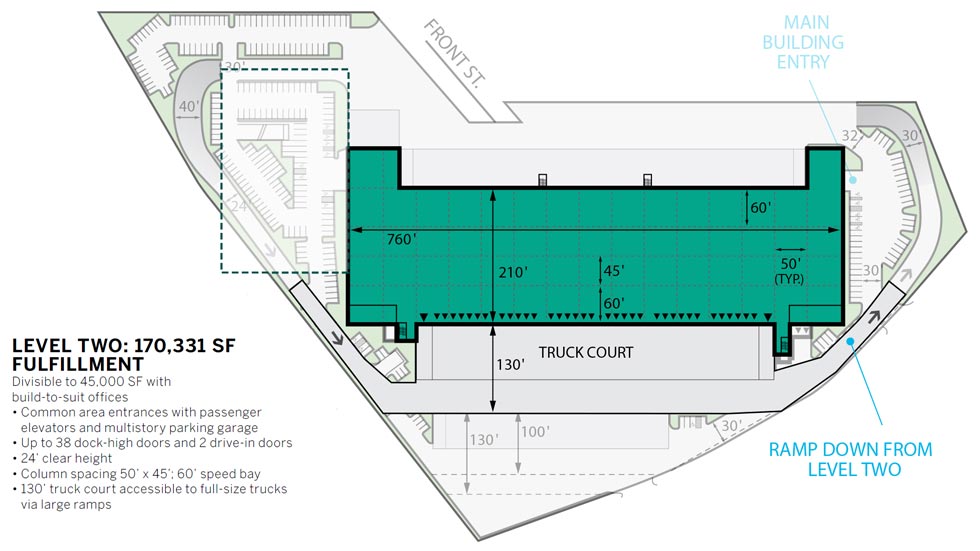

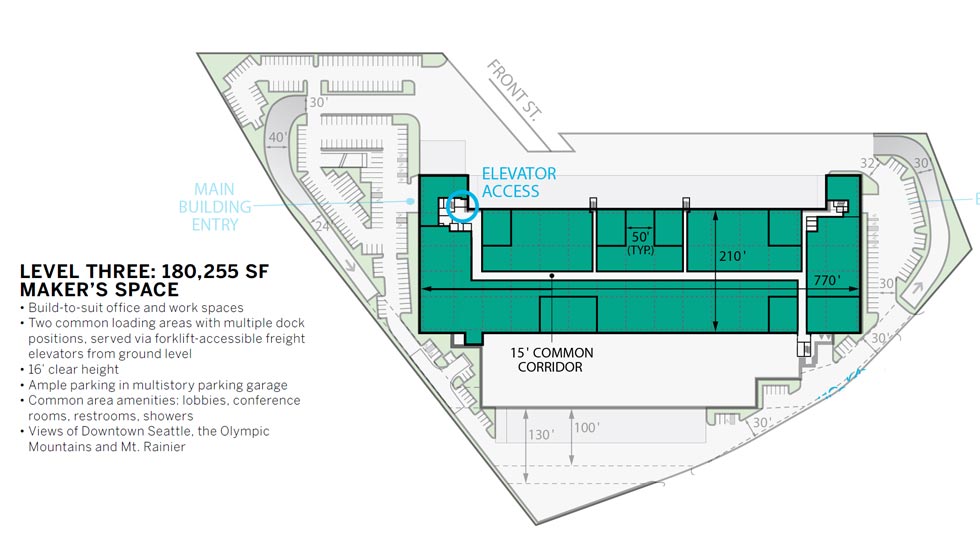

That said, Georgetown Crossroads offers 28-foot clear height for the first floor and 24 feet for the second floor, and easy access to nearby interstate highways. The building’s first floor has loading docks on both sides. The warehouse’s first two floors are able to handle standard, 53-foot-long tractor trailers. Two ramps serve the second floor, with the third level accessible by freight elevators that can hold forklifts. The third floor, with 16-foot heights, is suited for light manufacturing, creative offices, and production.

Build it and they will come

The fundamentals for multistory warehouses in major U.S. cities look good in part from a strong macroeconomic picture for industrial. Overall demand exceeds new supply, with net asking rents nationally having increased to $7.21 per square foot in the third quarter of 2018, up 1.7 percent from the second quarter. The pricing is the highest level since CBRE began tracking the metric in 1989.

However, in select infill markets rents can run much higher. CBRE estimates that Georgetown Crossroads is commanding $18 per square foot in annual rent, an 88 percent premium to the local market. Yet in the grand scheme of things, occupancy costs account for only 5 to 6 percent of total logistics expenses. Labor can represent 15 to 25 percent, and transportation, up to 75 percent. “Occupancy is marginal compared with everything else,” Walaszek says.

Population density will also certainly play a role in the economic viability of multistory distribution centers. Seattle has a density of 8,400 people per square mile, much higher than the next densest city of Dallas, at 3,900, according to CBRE research. The six other cities that are denser than Seattle include Los Angeles, Chicago, Miami, San Francisco, and New York, which tops out with a density of 28,000.

That said, developers pursuing multistory warehouses will need to have the capital to handle the expense of land acquisition and construction. The cost of facilities such as Georgetown Crossroads can run in the range of $150 million to $200 million, Moghadam notes. Prologis’ multistory project in San Francisco’s Bayview section, south of downtown, could total $500 million, with the addition of 1 million square feet to existing buildings there. “Our scale gives us the ability to try certain things that are very innovative, but more importantly, are vital to the success of our customers,” Moghadam says.

Build it and the tenants likely will come, Prologis and other developers are betting. While lots of e-commerce shipping is free, people will pay more to have same-day delivery, and more than 100 million customers globally already pay for Amazon Prime. This is all helping finance expensive land acquisition, building costs, and rents for retailers. It all bodes well for the nascent niche of multistory warehouses.