Triple-net lease REIT Realty Income has earned fans through a commitment to strengthening and paying its dividend monthly.

You’d forgive diners at a Taco Bell in Boise, Idaho, for focusing more on the bean burritos than who owns the splashy modern space painted in warm terra-cotta hues and decorated with high-end stone.

You’d forgive diners at a Taco Bell in Boise, Idaho, for focusing more on the bean burritos than who owns the splashy modern space painted in warm terra-cotta hues and decorated with high-end stone.

But the distinct building is a big deal in the REIT investment world because it’s part of the portfolio owned by Realty Income Corp. (NYSE: O), which owns buildings with leases of 10 to 20 years occupied by everyone from fast-food giants to gym operators. Realty Income might not generate as much attention as those that own landmark office buildings or sprawling shopping centers, but that doesn’t mean its success is less impressive or that investors haven’t taken notice.

Realty Income steadily climbed into the “upper echelon of the REIT world” and stayed there, says Simon Yarmak, who covers the company for Stifel. Adds Cedrik Lachance, Green Street Advisors’ director of U.S. REIT research: “It’s a well-managed company that, in the grand scheme of REITs, does a lot of things very well.”

Realty Income’s niche is single-tenant buildings in the triple-net lease segment, which means the tenant handles expenses like taxes, maintenance and insurance. The company has consistently delivered a strong dividend–even during the financial crisis–and maintained the respect of Wall Street, where attention can be fickle and fleeting. Even Jonathan Litt, who has made a name for himself as an activist investor in recent years, describes the company as respected, solid and well run.

What’s more, the company–which currently has an equity market cap topping $15 billion–is known for humility and approachability. Realty Income is “a big company, but it hasn’t changed the firm,” says Lachance, who has covered the company for more than two years and calls it the “blue chip” of its sector.

Such words make CEO John P. Case’s day.

“It’s nice to hear that people think of us that way,” Case says.

“We let the track record speak for itself, so we’re not out pounding our chests.

Founded on Dividends

Wall Street doesn’t care about being nice or not, but it does value Realty Income’s strong financial performance. In 2015, the company joined the S&P High Yield Dividend Aristocrats Index, putting it in the company of prestigious names including AT&T Inc., Caterpillar Inc. and Procter & Gamble. Not exciting enough? Last year, it was also added to the S&P 500.

Wall Street doesn’t care about being nice or not, but it does value Realty Income’s strong financial performance. In 2015, the company joined the S&P High Yield Dividend Aristocrats Index, putting it in the company of prestigious names including AT&T Inc., Caterpillar Inc. and Procter & Gamble. Not exciting enough? Last year, it was also added to the S&P 500.

What makes Realty Income stand out is a total return that consistently outpaces the FTSE NAREIT All Equity REITs Index, the Dow Jones Industrial Average and many other indexes. Since 1994, it has delivered a compound average annual return of 17 percent, outshining REITs’ 11 percent, the Dow Jones’ 9.8 percent and the S&P 500’s 9.3 percent for the same period, according to Realty Income. “We’ve done well growing the company’s earnings,” says Case, who joined the company in 2010 and became CEO in 2013.

Realty Income was founded in 1969, and its first acquisition was a single Taco Bell location. At that time, commercial banks weren’t comfortable financing new fast-food concepts as a certain burger chain was dominating the scene, Case said. Realty Income’s founders William Clark and Joan Clark, who still visit the company today, decided to raise money to buy Taco Bell locations, Case said.

The company went public in 1994 with a goal of providing investors with monthly dividends that increase over time. That appealed to everyday investors who liked the monthly income that has climbed from 7.5 cents per share in late 1994 to almost 20 cents per share earlier this year.

The dividend has remained steady, even in recent years as the housing and financial crises roiled the globe and depressed REIT stocks. Realty Income’s total payout is nearing $4 billion. Protecting the dividend has been essential to the company’s business model, and leadership has plenty to brag about: Approximately 550 consecutive dividends have been paid. There have been more than 80 dividend increases, with 70-plus consecutive quarterly increases and dividend growth of more than 150 percent since 1994. The compound average annual dividend growth rate is approximately 5 percent, according to the company.

The dividend has remained steady, even in recent years as the housing and financial crises roiled the globe and depressed REIT stocks. Realty Income’s total payout is nearing $4 billion. Protecting the dividend has been essential to the company’s business model, and leadership has plenty to brag about: Approximately 550 consecutive dividends have been paid. There have been more than 80 dividend increases, with 70-plus consecutive quarterly increases and dividend growth of more than 150 percent since 1994. The compound average annual dividend growth rate is approximately 5 percent, according to the company.

Case credits the sound and disciplined selection of high-quality real estate and tenants and a sound balance sheet as helping the company “sail through” the turbulent time without trimming the coveted payout or recapitalizing. Realty Income turns down many potential deals, he says.

“It’s gratifying to know that Realty Income performed for those investors, when many of them were experiencing losses in other sectors,” he says. “We continue to be good fiduciaries for our shareholders.”

The company’s stock also has caught the eye of institutional investors that may not be as dependent on the monthly income. Today, institutions own more than 60 percent of its stock. Even so, don’t expect the monthly dividend to go anywhere soon, given that many original and longtime retail shareholders remain loyal.

“Once you put your mother, your grandmother into a stock like this, they tend to hold it for a long period of time,” Yarmak says. “Some of the company’s net lease peers, I would tell you, are jealous of the fact that they have a strong, dedicated retail shareholder base.”

Case and others at the company work hard with the two distinct shareholder bases. “We want to make sure that we are listening to and in dialogue with both,” says Case, adding that the monthly dividend – whose growth shows a strong company – isn’t going anywhere anytime soon.

“The profile of a lot of our retail investors [is] retirees, aging baby boomers who are really income focused. That’s why they’re in the stock. They like something that’s very dependable.”

Tweaking the Business Model

Dedication to preserving and growing its dividend doesn’t mean that the company is resistant to change. It has refined its business model to supplement retail real estate, which can be fickle as brands go out of business and adjust to the rise of e-commerce.

Dedication to preserving and growing its dividend doesn’t mean that the company is resistant to change. It has refined its business model to supplement retail real estate, which can be fickle as brands go out of business and adjust to the rise of e-commerce.

Several years ago, Realty Income began a transition designed to address such threats. Such a strategy is “proactive and makes sense given that Internet sales continue to take market share,” Oppenheimer wrote when it initiated the company with an “outperform” rating in early 2014.

Realty Income addressed the potential long-run effects of e-commerce by increasing its concentration of tenants that specialize in services and non-discretionary goods and to improve the tenant quality. The shifts left Oppenheimer impressed: “The fact that [Realty Income] is addressing these issues now shows us the REIT is focused on long-term dividend security and growth.”

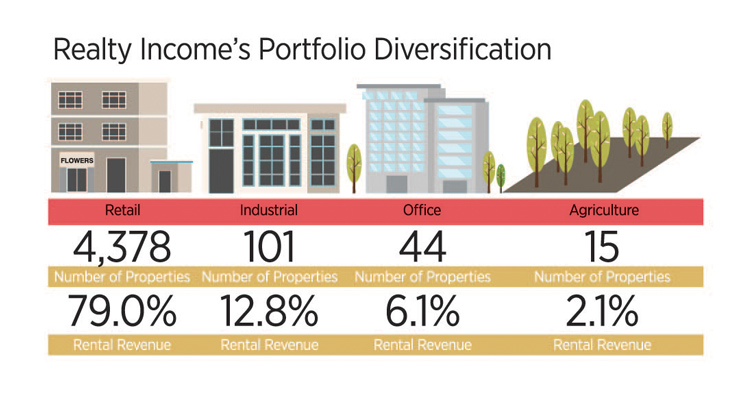

To be sure, retail remains a big part of Realty Income’s portfolio — nearly 80 percent. Its largest tenant is drug store chain Walgreens at roughly 7 percent, while the discount stores Dollar General, Dollar Tree and Family Dollar combine for nearly 9 percent of the portfolio. There’s also BJ’s Wholesale Club, Walmart and Sam’s Club, according to the company.

“No matter how good a tenant may wind up being, strange things can bring down companies,” says Rob Stevenson, who covers the company for Janney Montgomery Scott LLC. “Even if you’re sure that someone is a quality tenant today, you don’t know what’s going to happen five, 10 years down the road.”

More than Retail

That’s one reason that Realty Income stresses that it is more than a pure-play retail company. Its portfolio spans 49 states and Puerto Rico, boasting 240 commercial tenants across 47 industries, including industrial, office and agriculture. Drill deeper into securities filings and the company lists everything from health care to motor vehicle dealerships–businesses less likely to be disrupted by the Internet. The company recently reported occupancy of 98.4 percent, showing minimal vacancies.

That’s impressive, given that the company’s clients like to rent buildings that make their brands identifiable. Taco Bell has a certain look that’s different from a Pizza Hut, for example, so re-leasing becomes tougher if a tenant vacates.

That’s impressive, given that the company’s clients like to rent buildings that make their brands identifiable. Taco Bell has a certain look that’s different from a Pizza Hut, for example, so re-leasing becomes tougher if a tenant vacates.

That makes buying prime locations key, Lachance says. “Truly, truly distinctive buildings don’t make for great net-lease investments because of the cap-ex that would be required in a change of tenancy,” he explains. “The ability to repurpose the space is typically dependent on the quality of the location.”

Case agrees. Location is paramount, he says, but so are companies in industries with staying power. The same goes for finding tenants that will perform well during the economy’s ups and downs and compete with the likes of Internet retailer Amazon, which has turned e-commerce into a point-and-click shopping experience with rapid delivery. Case cites an auto-service tenant as a perfect example. It’s difficult for the Internet to replicate this service.

The company is dedicated to tenants and willing to share the costs of remodels.

The company is dedicated to tenants and willing to share the costs of remodels.

Theaters, for example, are taking out tiny seats and adding in more comfortable seating and food options. Those changes increase income – and rent.

“We’ve got a great relationship with tenants,” Case says. “If they want to change their concept… they’ll come to us.”

Another key to this business model is underwriting the tenants well and sharing that with analysts who are eager to know just who is leasing all this space. Public tenants are easy to research and assess, but the finances of private players can stump analysts. (The company gets plenty of data on most of its tenants.) Realty Income itself has worked to become more transparent. Its website boasts the credit quality of several tenants.

“These guys do a ton of work underwriting the credit quality of the tenant,” Stevenson says. “Anyone can underwrite Apple. Where it takes the expertise is in underwriting non-public guys.”

Case doesn’t think investors should expect any major strategy shifts this year. One analyst dubbed the company a “SWAN” REIT, which stands for “sleep well at night.” Case is fine with that.

After all, “the strategy has been working quite well,” he says.