Research says pension funds are leaving returns on the table by under-allocating to REITs.

As baby boomers grow older, an estimated 10,000 Americans are retiring every day. That is putting mounting pressure on defined benefit pension plans to provide the steady income and capital appreciation necessary to meet their financial obligations.

Of the $24 trillion in retirement assets in the United States as of the end of 2015, about a third belonged to public and corporate pension plans. Real estate has long been a staple of these defined benefit funds’ portfolios, but are those allocations producing enough bang for the buck?

Nareit-sponsored research from Toronto-based investment consultant CEM Benchmarking indicates they are continuing to fall short in part due to underweighting REITs.

How Many Pension Funds Invest in REITs?

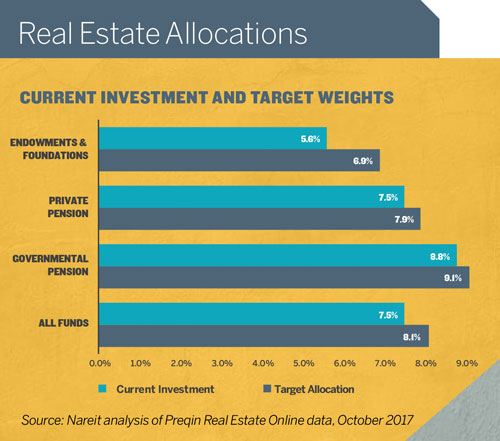

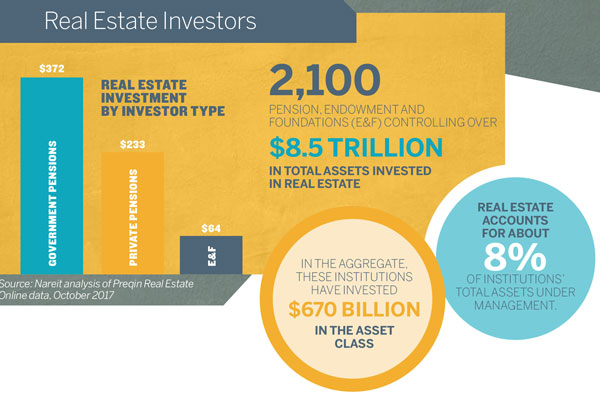

According to a Nareit analysis of data from Preqin, a financial research firm that tracks investment in alternative assets, some level of REIT investment is broadly based among government and private pension funds, endowments and foundations, which have a little more than $600 billion invested in real estate in the aggregate. More than 35 percent of these investors, on an asset-weighted basis, use REITs as part of their real estate portfolio. That equates to 40 percent of pension funds by number.

According to a Nareit analysis of data from Preqin, a financial research firm that tracks investment in alternative assets, some level of REIT investment is broadly based among government and private pension funds, endowments and foundations, which have a little more than $600 billion invested in real estate in the aggregate. More than 35 percent of these investors, on an asset-weighted basis, use REITs as part of their real estate portfolio. That equates to 40 percent of pension funds by number.

How Big Are Institutional Investors’ Allocations to REITs?

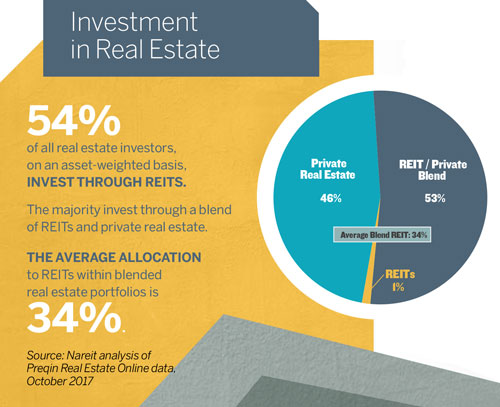

The data are a little murky. However, the Preqin numbers analyzed by Nareit show that of those that invest in real estate,

53 percent include allocations to REITs along with private real estate as part of their real estate portfolios. Within those blended portfolios, the average allocation to REITs was 34 percent.

In the entire universe of pension funds, endowments and foundations, REITs comprise approximately 19 percent of the total investment in real estate.

Are Pension Funds’ Allocations to REITs Large Enough?

The updated CEM study suggests they are not.

“Listed equity REITs once again emerged as the study’s top-performing asset class with the highest average annual net return; relatively low correlations with other asset classes, implying good diversification benefits; and superior risk-adjusted returns,” says CEM Benchmarking Senior Research Analyst Alexander Beath, who authored the study. “Despite the asset class’ sustained, measurable outperformance over the past 18 years, REITs continue to represent only 0.6 percent of total pension fund asset allocations, highlighting a significant missed opportunity to generate substantial returns with lower annual investment costs.”

“Listed equity REITs once again emerged as the study’s top-performing asset class with the highest average annual net return; relatively low correlations with other asset classes, implying good diversification benefits; and superior risk-adjusted returns,” says CEM Benchmarking Senior Research Analyst Alexander Beath, who authored the study. “Despite the asset class’ sustained, measurable outperformance over the past 18 years, REITs continue to represent only 0.6 percent of total pension fund asset allocations, highlighting a significant missed opportunity to generate substantial returns with lower annual investment costs.”

Anecdotally, asset managers say their experience matches up with the CEM research.

“We think the allocations when measured as a percentage of the overall real estate allocation or as a percentage of the plan are still light relative to the benefits they provide,” says Geoff Dybas, head of Duff & Phelps Global Real Estate Securities team.

Scott Crowe, chief investment strategist and portfolio manager with CenterSquare Investment Management, estimates that defined benefit plans are split roughly down the middle in terms of those that view REITs as essentially proxies for direct ownership of real estate assets. All in all, pension plans’ underallocations to REITs stand out even more “considering that REITs own some of the best real estate in the world,” according to Crowe.

Scott Crowe, chief investment strategist and portfolio manager with CenterSquare Investment Management, estimates that defined benefit plans are split roughly down the middle in terms of those that view REITs as essentially proxies for direct ownership of real estate assets. All in all, pension plans’ underallocations to REITs stand out even more “considering that REITs own some of the best real estate in the world,” according to Crowe.

“I think that half the [defined benefit plan] market remains too closed minded as it relates to REITs,” he says.

What Is Keeping Defined Benefit Plans From Embracing REITs?

Historically speaking, the knock on REITs in the defined benefit community is their volatility, or as Andy Rubin, institutional portfolio manager for Fidelity, puts it, REITs are perceived as being “too stock-like.”

“The perennial argument always exists between measured and realized volatility,” Crowe says. “There are some investors that basically don’t treat [REITs] as real estate because [they have] daily pricing, and I think that segment of the market will always exist.”

The fact that REITs are public equities means they are subject to some of the “noise” that affects the broader investment market, according to Rubin. However, he points that the arguments change over the longer holding periods customary to defined benefit plans.

The fact that REITs are public equities means they are subject to some of the “noise” that affects the broader investment market, according to Rubin. However, he points that the arguments change over the longer holding periods customary to defined benefit plans.

“Academic study after study have certainly confirmed that over appropriate length periods… that a lot of that shortterm noise sort of comes out in the wash,” Rubin says.

Will REITs Eventually Play A Larger Role In Pension Funds’ Real Estate Allocations?

Despite the historic under-allocation to REITs among pension plans, investment managers maintain that opinions in the space are changing.

“We believe that the view on REITs has clearly improved over time as a recognition of their benefits has come to light,” Dybas says.

In addition to a recognition of the investment benefits of REITs, the growth of the listed REIT market in size, depth and breadth has played a key role in calling attention to the industry, according to Rubin. Notably, in 2016, S&P Dow Jones Indices and MSCI elevated stock-exchange listed real estate companies from under the Financials Sector to a new 11th headline Real Estate Sector under the Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS). Rubin also points out that REITs offer exposure to segments of the commercial real estate market that aren’t available through traditional private real estate investment, such as data centers and cell towers.

In addition to a recognition of the investment benefits of REITs, the growth of the listed REIT market in size, depth and breadth has played a key role in calling attention to the industry, according to Rubin. Notably, in 2016, S&P Dow Jones Indices and MSCI elevated stock-exchange listed real estate companies from under the Financials Sector to a new 11th headline Real Estate Sector under the Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS). Rubin also points out that REITs offer exposure to segments of the commercial real estate market that aren’t available through traditional private real estate investment, such as data centers and cell towers.

Overall, Dybas says the firming of positive sentiment by pension plans and appreciation for the investment attributes of REITs should continue to bring larger allocations to the REIT space. “We think the future actually is a prosperous one for the underlying plan beneficiaries and participants to the extent there is an increased addition to the REIT allocation.

What CEM Found

The new CEM research is actually an update of a study first published in 2016 that analyzed data from 1998 to 2014 on the impact of asset allocations on the investment performance of more than 200 large pension funds holding a combined $3.4 trillion in assets under management. The updated study covered 200 public and private pension funds over the 18-year period from 1998 to 2015. In total, the funds included in the new study control approximately $3.5 trillion in assets.

CEM broke down the funds’ assets into 12 different categories to calculate their average annual net returns. The objective: analyzing the actual investment performance of the funds, not benchmark returns.

Some of the key CEM findings were:

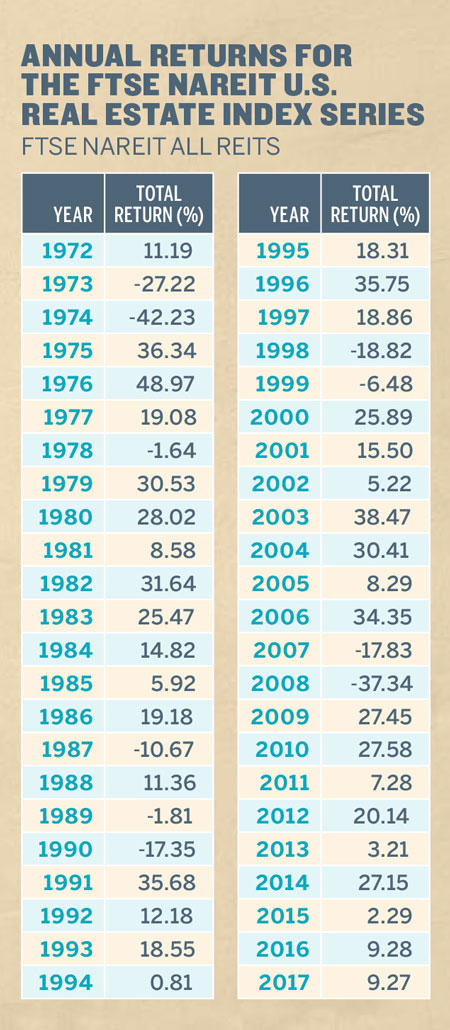

- Listed REITs had an average annual net return of 11.4 percent across the period, the highest of any asset class.

- Listed REITs have low fees. Relatively low fees of 50 basis points—half of private real estate—contributed to listed REITs’ broader outperformance.

- Listed REITs and unlisted real estate assets display similar levels of volatility. Once the CEM researchers adjusted for reporting lags and variation in returns across pension plans, listed REITs had net returns with volatility of 20.3 percent for the 18-year period, while unlisted real estate’s volatility was 18.8 percent.

- Listed REITs and unlisted real estate show low correlations to the other asset categories.

- Listed REITs and unlisted real estate are highly correlated and show that an investment in REITs is an investment in the real estate asset class.

- Outside of fixed-income assets, REITs had the highest risk-adjusted returns. Excluding the fixed-income category, REITs had the highest Sharpe ratio among all the asset classes 0.44, which reflects the asset class’ strong returns and moderate average volatility. Unlisted real estate had a much lower Sharpe ratio, 0.31, reflecting lower returns and comparable volatility to REITs.

- Listed REITs were the least used asset class of those involved in the study. Allocations to listed REITs within the pension plans averaged 0.6 percent of total assets. Conversely, investment in direct and other private real estate investments had an average allocation of 3.5 percent, despite producing average annual net returns of 8.7 percent; nearly 300 basis points lower than that of REIT investments.

What Do REITs Bring to Defined Benefit Portfolios?

Investment managers maintain that REITs offer a number of investment attributes that benefit pension funds.

Investment managers maintain that REITs offer a number of investment attributes that benefit pension funds.

Dividend Income

REITs must distribute at least 90 percent of their taxable income to shareholders as dividends, which have given investors a reliable source of income over time.

These dividends can help pension plans fund their retirement benefit payments to beneficiaries.

Liquidity

Whereas direct real estate owners can find it difficult to divest their interests in their holdings, REITs provide a liquid form of real estate investment. Like all owners of REIT stocks, defined benefit plans can buy and sell their shares on the market with ease.

“Providing liquidity is a critical role,” Dybas says. “Many of the pension funds that have embraced REITs have have been attracted to the liquidity that REITs afford investors in an asset class like commercial real estate that can be rather illiquid,” Rubin says.

Diversification

By investing in REITs, pension plans can round out their portfolios with an asset class that has a history of low correlation to the movements of the broader investment market. REITs respond to a different set of economic drivers and signals than other assets in the investment portfolio.. In turn, this has a smoothing effect on a diversified portfolio’s overall volatility.

Competitive Long-Term Performance

REITs’ history of long-term capital appreciation and delivering dividends have offered competitive returns relative to the rest of the investment universe. “The performance that REITs have generated over very long periods of time is really a superior commercial real estate return net of fees versus private real estate vehicles,” Rubin says.

“Over the long term, REITs have produced returns at or above private real estate returns because they own some of the best real estate in America and are managed by some of the best management teams in the world,” Crowe says.

Transparency and Governance

REITs provide investors the transparency of investments listed and traded on public markets. For pension fund managers with fiduciary responsibilities, this offers peace of mind.

Additionally, Dybas notes that as a growing number of defined benefit plans zero in on the environmental, social and governance (ESG) aspects of their investments, which should also make REITs appealing. “REITs allow pension plans to leverage their ongoing increased focus on sustainability as so many REITs are now increasingly focused on ESG, issuing robust sustainability reports as examples of their increased focus,” he says.